No Half Measures: Software Craftsmanship

Half-implemented features accumulate technical debt that compounds over time. The Mars Climate Orbiter crashed from skipping a unit conversion check. Software craftsmanship means building systems that work reliably and can be maintained by others.

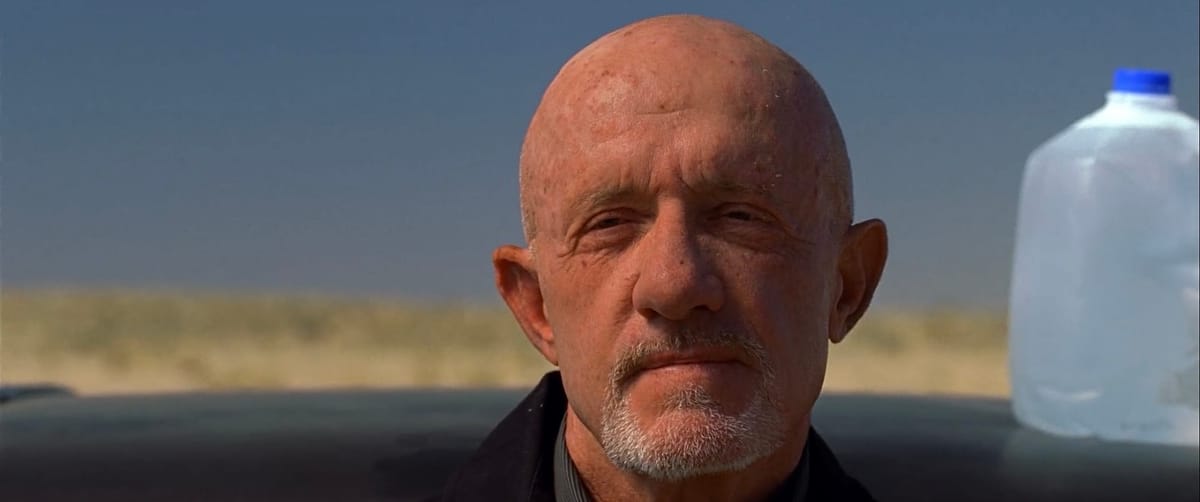

"No half measures" might sound like tough-guy rhetoric from Breaking Bad, but Mike's philosophy cuts to the heart of a fundamental truth about quality work: incomplete solutions create more problems than they solve. Let me use that as an analogy to software.

The Compounding Cost of Half Measures

Half-implemented features don't stay half-implemented. They accumulate what researchers call "technical debt" shortcuts that seem expedient but accrue interest over time, making future changes exponentially more difficult and costly.

Google studied 117 different metrics trying to predict technical debt and reached a sobering conclusion: there's no single indicator that tells you when your shortcuts are about to collapse your codebase. The decay happens gradually, then suddenly.

The most spectacular software failures often trace back to seemingly minor shortcuts:

Mars Climate Orbiter: $125 million spacecraft crashed because engineers skipped a simple unit conversion check between metric and English measurements.

Ariane 5 Rocket: $370 million explosion caused by reusing code from Ariane 4 without accounting for different data size requirements. A 64-bit number couldn't fit in a 16-bit space.

Healthcare.gov: Hundreds of millions spent on a system that couldn't handle basic user registration because integration testing was treated as optional.

What Going All the Way Actually Means

Software craftsmanship isn't about perfectionism or gold-plating features. It's about professional thoroughness: building software that works reliably, can be maintained by others, and handles edge cases gracefully.

The Software Craftsmanship Manifesto puts it simply: "Not only working software, but also well-crafted software." This means:

Edge Case Obsession: Your software works not just for happy path scenarios, but for the 5% of cases that reveal true system quality. Error states are designed as carefully as success paths.

Code That Communicates: Future developers (including yourself in six months) can understand what you built and why. Comments explain decisions, not just implementations.

Testing as Design: Tests aren't afterthoughts: they're specifications that ensure your code does what you think it does.

Architectural Integrity: Each component has a clear purpose and defined boundaries. Dependencies flow in logical directions.

This isn't about spending infinite time polishing code. It's about building habits that make quality the default outcome.

The Feature Factory Problem

Most development teams operate like feature factories: measure output by story points completed, celebrate shipping dates, and treat maintenance as someone else's problem. This approach optimizes for short-term delivery at the expense of long-term sustainability.

The result is what practitioners call "Agile hangover". Teams that ship regularly but accumulate technical debt faster than they can pay it down. Features take longer to implement. Bugs multiply. Developer productivity plummets.

70% of digital transformation projects fail, with 70% of those failures traced to requirements issues. Teams rush to build before they understand what they're building, then spend months fixing the inevitable misunderstandings.

The Craftsmanship Alternative

Software craftsmen approach development differently. Instead of maximizing output, they optimize for outcomes. Instead of rushing to ship, they take time to understand the problem fully before proposing solutions.

This isn't slower development—it's more effective development. Research shows the most successful projects don't rely solely on testing to catch defects. They prevent defects through documented designs, thorough requirements review, and code inspections before implementation begins.

Quality practices that matter:

- Pair programming: Two developers working together catch errors in real-time and share knowledge

- Test-driven development: Writing tests first forces clear thinking about what code should do

- Code reviews: Fresh eyes catch issues the original author missed

- Refactoring: Regularly improving code structure prevents decay

These practices seem expensive upfront but pay dividends over time. Clean, well-tested code is easier to modify, debug, and extend.

The Old-Fashioned Value of Seeing Things Through

Call it old-fashioned, but there's profound satisfaction in building something well. Taking pride in craft rather than just meeting deadlines. Software development is creative work that deserves the same attention to detail as any other craft.

This doesn't mean perfection. It means professionalism. It means taking responsibility for the long-term consequences of your decisions. It means asking "Is this how I'd want to find this code if I had to maintain it?"

The craftsman mindset recognizes that software isn't just about solving immediate problems, it's about creating systems that can evolve and adapt over time. This requires thinking beyond the current sprint or release cycle.

Becoming a Craftsman

You don't become a software craftsman by reading books or attending conferences. You become one by practicing the craft daily and holding yourself to higher standards than anyone else requires.

Start with your next feature. Before you write code, understand the problem completely. Design the solution carefully. Write tests that document your intent. Implement cleanly. Review your work critically. When you encounter existing technical debt, don't just work around it, fix it. Leave code better than you found it. Make the invisible work visible to your team.

The craftsmanship movement spreads through demonstration, not argument. Become the developer others want to work with because your code is reliable, readable, and well-designed. Let your work speak for the value of going all the way.

In a world of shortcuts and quick fixes, choosing the craftsman's path is both a professional decision and a personal one. It's the difference between being someone who writes code and someone who builds lasting value.

No half measures. Complete commitment. That's how software should be built.

Comments ()