How Money Took Over American Politics

1. Why money in elections is a problem

American elections now run on a scale of money that would have been unthinkable a generation ago.

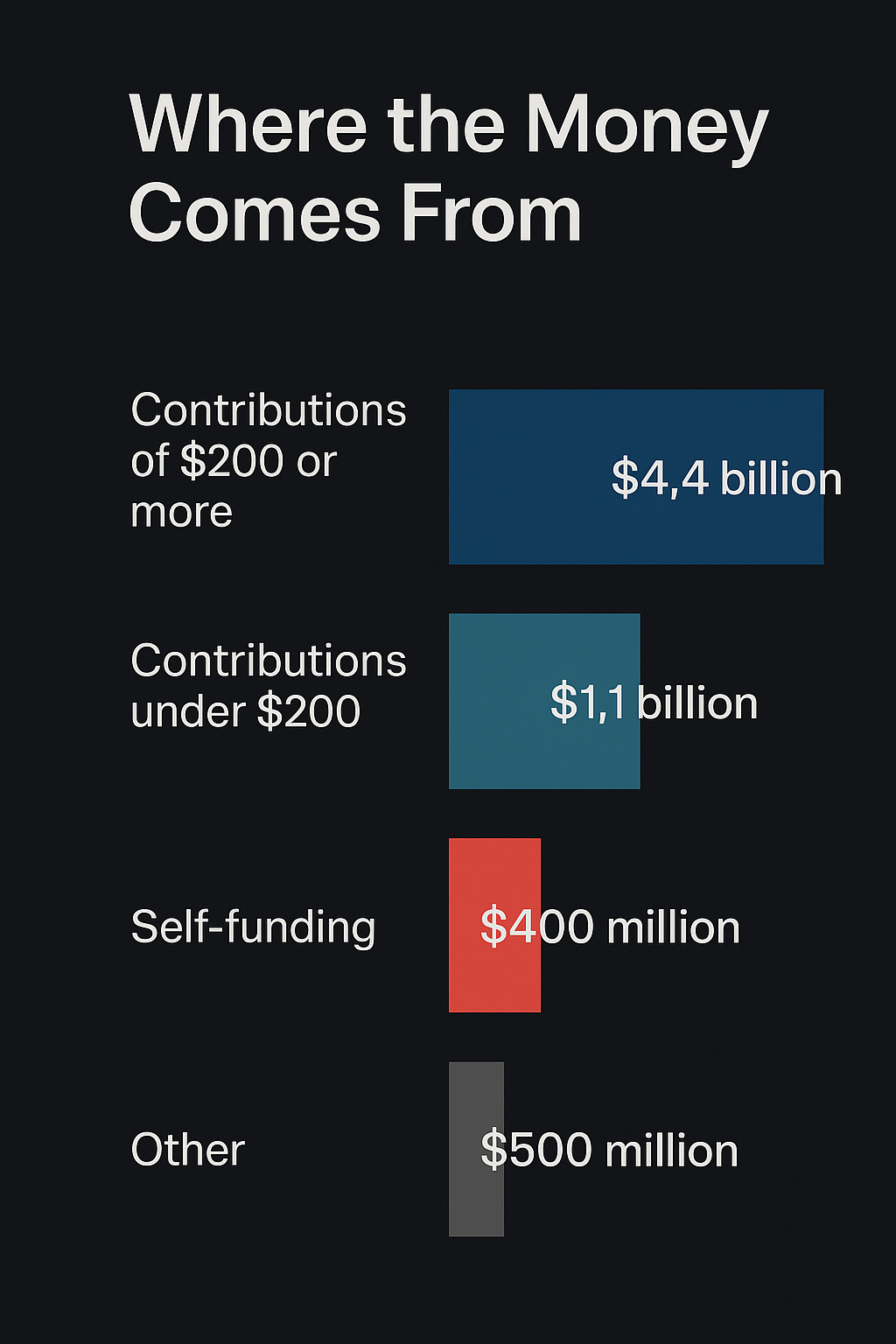

- The 2024 federal election cycle is estimated at about 16 billion dollars in total spending, with about 10.2 billion on congressional races and 5.5 billion on the presidency. (OpenSecrets)

- Outside groups such as super PACs have already spent over 2.6 billion dollars influencing the 2024 cycle. (OpenSecrets)

Money does not guarantee a win in every single race, but it is very close to a winning ticket most of the time:

- Historically, the better financed House candidate wins about 90 percent of the time, and the better financed Senate candidate wins about 80 percent of the time. (Social Sci LibreTexts)

Why that matters:

- Attention and name recognition Ads, field operations, data targeting, and social media all cost money. Voters cannot evaluate a candidate they never see or hear from. The candidate who can afford to stay in front of voters usually defines the narrative.

- Gatekeeping and viability Donors, party committees, and media treat fundraising totals as a proxy for “serious” or “viable.” If you cannot raise big money early, you often never get taken seriously enough to build the support that would let you raise more.

- Representation skew When winning is tightly linked to fundraising, policy tends to track the preferences of those who fund campaigns. It is not subtle. A landmark study of 1,779 policy issues by Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page found that economic elites and business interest groups have substantial independent impacts on U.S. policy, while average citizens have little or no independent influence. (Cambridge University Press & Assessment)

So the money problem is not abstract. The way we finance campaigns shapes who wins, what gets debated, and whose interests actually show up in law.

2. Key legal shifts: corporations, speech, and elections

The current flood of money did not come out of nowhere. Courts and Congress created it. Three decisions are the core of the modern problem.

Buckley v. Valeo (1976): money as speech

After the post Watergate Federal Election Campaign Act tried to control both contributions and spending, the Supreme Court split the difference.

- The Court upheld limits on contributions to campaigns.

- It struck down limits on campaign expenditures by candidates and independent groups, treating spending on political communication as protected speech under the First Amendment.

That decision locked in the basic equation: spending is a form of speech. If you have more money, you effectively have a larger megaphone.

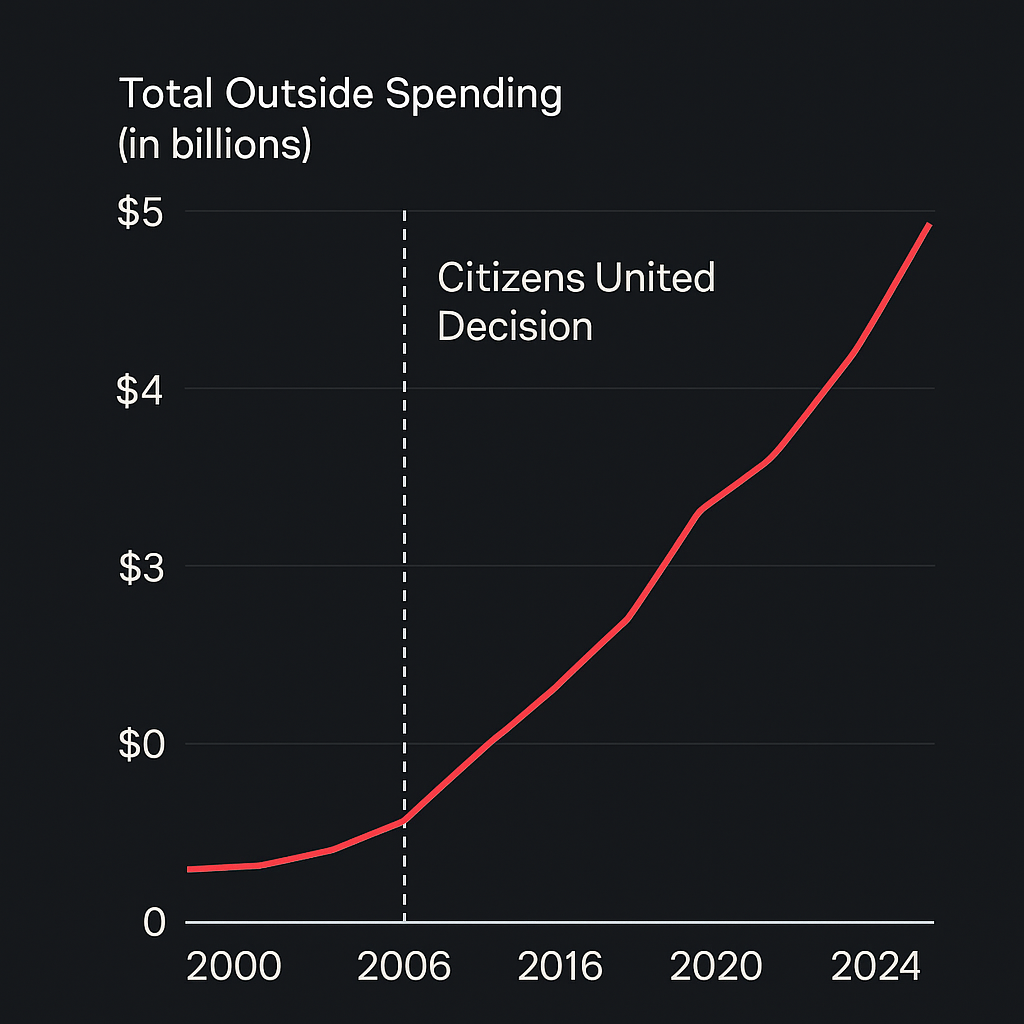

Citizens United v. FEC (2010): corporate and union spending unleashed

Citizens United is the real turning point in the modern era.

- The Court held that corporations and unions have a First Amendment right to spend unlimited money on independent expenditures for or against candidates, as long as they do not coordinate directly with campaigns. (Brennan Center for Justice)

- This knocked out key parts of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (McCain Feingold), which had restricted “electioneering communications” by corporations and unions close to elections. (Brennan Center for Justice)

The result was predictable. Outside spending blew up.

- A Brennan Center analysis found that outside spending more than doubled in the election cycles immediately after Citizens United. (Brennan Center for Justice)

- By the 2024 cycle, dark money groups and shell nonprofits poured over 1.9 billion dollars into federal races, almost double the previous record of about 1 billion in 2020. (Brennan Center for Justice)

- Another Brennan Center report argues that fifteen years later, Citizens United has given corporations and billionaire backed super PACs a central role in U.S. elections and made dark money a permanent feature of the system. (Brennan Center for Justice)

So now you have a world where a corporation, a trade association, or a single billionaire can drop tens or hundreds of millions into the information environment around a race. They do not have to coordinate with a candidate to shape the entire battlefield.

McCutcheon v. FEC (2014): mega donors get a green light

- Before McCutcheon there were limits on how much total money one person could give in a cycle across all federal candidates and committees.

- The Court struck those aggregate limits down, which made it much easier for a small number of ultra wealthy donors to spread huge sums across entire party networks nationwide. (Brennan Center for Justice)

Combine Buckley, Citizens United, and McCutcheon and you get the modern system:

- Money is speech.

- Corporations, unions, and nonprofits can spend unlimited amounts independently.

- Wealthy individuals can legally push very large sums across many races and committees.

3. How elected officials actually spend their time

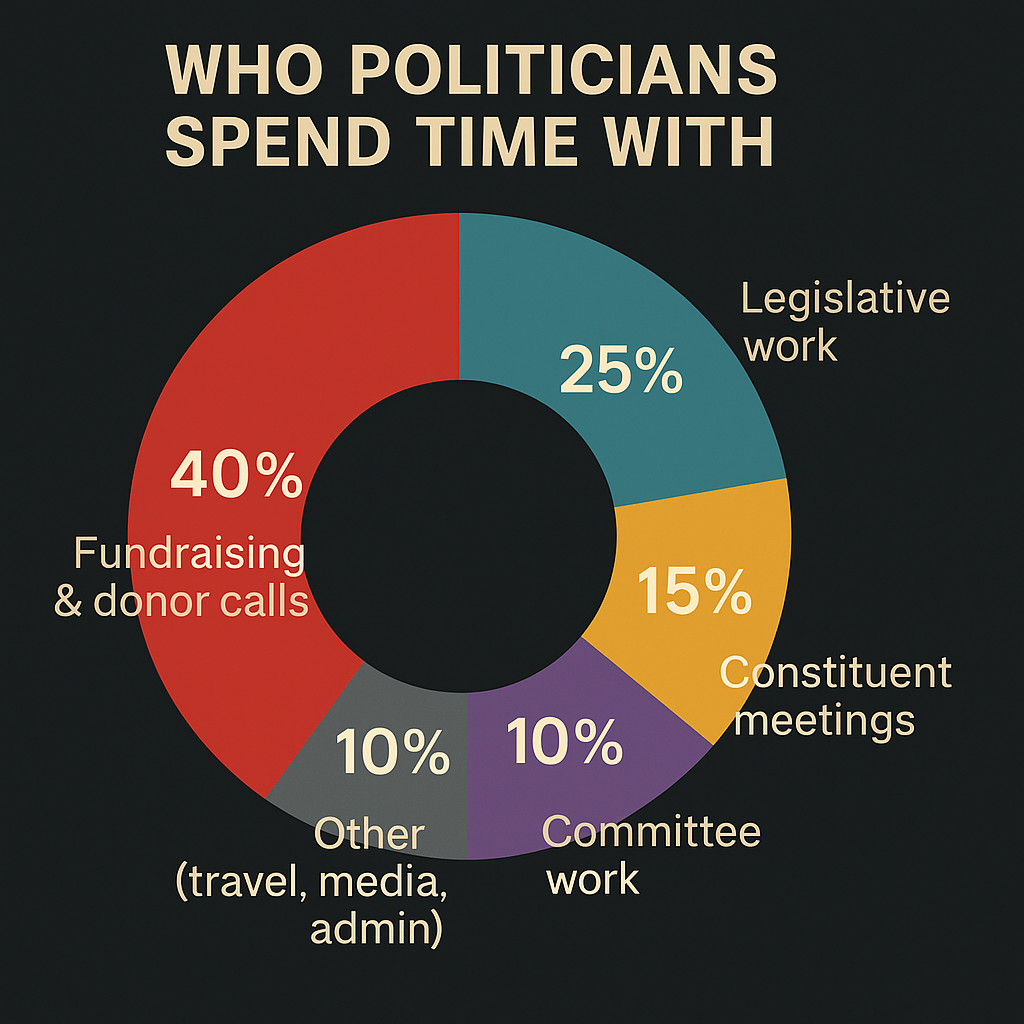

Once money becomes the fuel of survival, governing time gets cannibalized by fundraising.

Multiple investigations, academic work, and even party training materials paint the same picture:

- A widely reported training slide from party leadership told new members of Congress to spend about four hours per day on “call time” and fundraising related work. (The Washington Post)

- Legal scholarship and analysis of campaign finance patterns describe fundraising as a central part of the job. One paper in the Seton Hall Legislative Journal calls the modern Congress dominated by the fundraising treadmill, with ongoing increases in the amounts House and Senate candidates must raise, especially after 2010. (Seton Hall eRepository)

- A 2024 Brennan Center analysis of congressional fundraising describes how financial demands now shape the pathways to power in Congress, from who can run, to who can chair committees, to who gets leadership roles. (Brennan Center for Justice)

The practical effect:

- Member schedules tilt toward donors When you have to raise millions every cycle, you spend your working hours with people who can give in large amounts. That usually means corporate PAC representatives, lobbyists, and wealthy individuals.

- Agenda setting is skewed If you want a bill to move, it helps if it excites or protects major donors and aligned interest groups. If it only helps ordinary people who cannot write checks, it is more likely to sit.

- Policy outcomes mirror elite preferences Gilens and Page show that when the preferences of average citizens conflict with those of economic elites and business groups, elites usually win. (Cambridge University Press & Assessment)

This is not usually the old school bribery image. It is a structural addiction. If your reelection depends on people who can wire six or seven figure sums, you act accordingly.

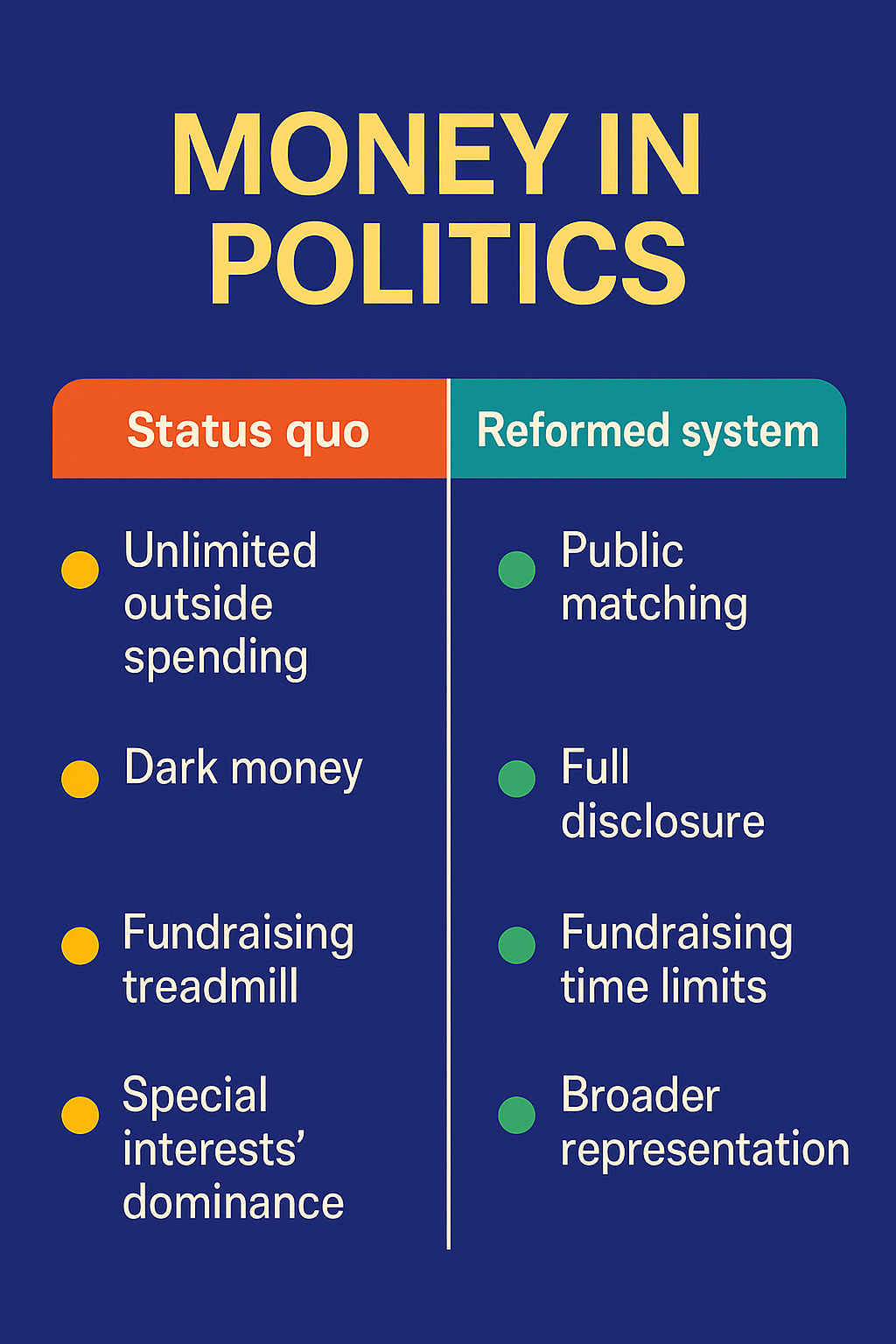

4. We need to get money out of politics

If you want a democracy where regular people matter, you cannot let elections be dominated by those who can spend the most. Getting money out of politics is not one silver bullet, it is a package of structural changes.

Concrete moves that are already tested or actively proposed:

- Public financing that boosts small donors

- Systems like New York City’s small donor match multiply a 20 or 50 dollar donation by as much as eight to one. This lets a candidate build a competitive campaign on hundreds or thousands of small donors instead of a few check writers. (Times Union)

- Real transparency for every dollar spent

- Close the loopholes that let dark money nonprofits and shell entities hide the true source of spending. The Brennan Center documents how dark money has hit record levels and argues for stronger disclosure rules. (Brennan Center for Justice)

- Directly confronting Citizens United

- A long list of states and cities have already voted to support a constitutional amendment to overturn Citizens United. (Brennan Center for Justice)

- Short of an amendment, Congress can still tighten coordination rules, increase disclosure, and create strong public financing options that make big money less decisive.

- Limits on fundraising while governing

- Ban or sharply restrict fundraising when Congress is in session. Members should not be sprinting out of hearings to call donors. Structural time rules would force more actual governing and less phone banking.

- Free or low cost access to voters

- If candidates had guaranteed blocks of public media time and cheap ballot access, they would not be as dependent on raising cash just to be visible.

The basic choice is simple. Either we leave the system as is and accept a politics where wealth buys volume and access, or we change the rules so that votes and small donors matter more than checks with five zeros.

Comments ()